Small Business Tax Basics Explained: Taxes 101

There’s no avoiding small business taxes. (Even attempting it probably means jail time, and it’s hard to keep an eye on the help or keep up with industry trends when you’re serving a long-term prison sentence. Plus, they’ll take them anyway. It’s really much better just to pay them as you go.) It is possible, however, to make things a bit easier on yourself with a little planning ahead and attention to a few key things as you take care of business each week. It’s possible to make things much harder on yourself as well – for instance, if you try really hard not to think about taxes until they’re due (or past due).

Let’s look at a few small business tax basics and see what we can do to keep your blood pressure down and your lawyer bored.

Rule #1 of Small Business Tax Basics

Most basic small business tax management can be done by anyone with a high school education and willing to devote the necessary time and energy while paying attention to the small print. But just because you could do it yourself doesn’t mean you should. Entrepreneurs have a wide variety of gifts and passions, but nothing says tax codes and number juggling have to be among them.

I can cook well enough to survive. I don’t have a real passion for it, but some of what I make is pretty decent. For special occasions, I have a few “go to” dishes which are reasonably impressive, as long as I never invite the same people to dinner a third time.

But you know what I prefer when I want a good meal? Eating out. Local diners. Chain restaurants. Pizza delivery. It’s always just as good as usually better than what I’d make at home, and even though I’m paying someone else to make food for me, it’s worth it because that’s what they do. They’re experts. That way, I can focus more on the things I care about. Plus, if something goes wrong – the food is burnt, the order is wrong, or a drink is spilled – that’s on them. They have to fix problems and deal with cleanup. That’s the gig.

So, let’s just say up front that there are endless advantages to having someone qualified take care of your small business taxes. While you can’t exactly just go to the tax store and buy “completed taxes,” you don’t have to go it completely alone, either. If you choose not to turn everything over to a professional, consider at least utilizing some of the better online tax tools which are available in the 21st century. Neither option means you shouldn’t still educate yourself on what’s going on.

I assume when you order “Burrata Tortelloni,” you’d at least like to know whether you’re about to try a tomato-based pasta or a very expensive wine, yes? It’s the same with knowing your small business tax basics.

Small Business Structures

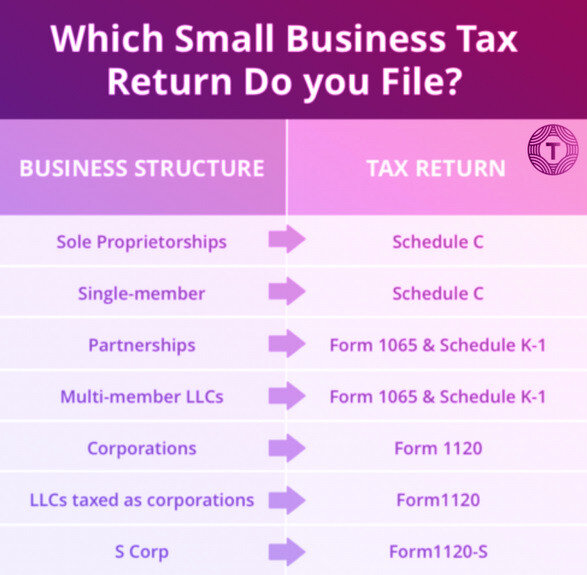

The type of small business you have is the single biggest factor in what sort of taxes you’ll be paying. By “type,” of course, I don’t mean whether you do magic and balloon animals for children’s birthday parties or manufacture specialty rims for sports cars. I mean how your business is structured legally and organizationally. Let’s recap the most common options and highlight the tax implications of each.

Sole Proprietorships

This is just what it sounds like – a small business structure in which you are the business and the business is you. You make all of the decisions, you control all of the profits, and you eat any of the losses or liabilities. With great power comes great responsibility, Entrepreneur-Man (or Woman).

Taxes for a sole proprietor aren’t dramatically different than what you’re doing as an individual taxpayer already. Your business income is taxed at your personal income rate, the same as if you earned it working for someone else. Because your business isn’t taxed separately as a business, you’ll sometimes hear income from sole proprietorships or similarly structured businesses called “pass-through income,” or the businesses referred to as “pass-through businesses.” That’s because the profits “pass through” to your personal income totals for purposes of taxation.

Of course, if potential profits are all yours, so are potential losses, as well as the responsibility for normal debts or operating costs along the way. Because many small businesses utilize a variety of small business loans to facilitate growth and smooth operations, it matters very much whose name is on the bottom line of that paperwork.

Incidentally, as of the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) which took effect last year, many sole proprietors can deduct up to 20% of what would otherwise be taxable income from your small business. In other words, if your small business made $50,000 total profit last year – profit which as a sole proprietor you’d need to claim as income on your Form 1040 – there’s a good chance you can knock $10,000 off of that for purposes of figuring your taxable income. The TCJA made other changes as well, some of them a bit tedious to unravel and applying only in very specific circumstances. You can see how the I.R.S. explains it here (pages 34 - 37).

The goal was to keep things simple (although it’s still the federal government and “simple” is a relative term). Still, in terms of small business tax basics, if it’s just you – no partners, no employees – the sole proprietorship is the easiest and most practical route in most cases. When it’s time to pay Uncle Sam, rather than file entirely separate tax returns for your business, you’ll complete a few extra forms along with your standard Form 1040. And you were doing one of those anyway, right?

Your Friend, schedule c

The first of these is the Schedule C. It’s one page, front and back, and primarily a worksheet for determining how much profit you made during the year in question. It allows you to itemize business expenses and deduct many of them from the income you report. Total income minus expenses equals profit, at least on paper.

The Schedule C is one reason it’s so beneficial to keep track of mileage and receipts throughout the year. Of all the clever tax tips or other strategies we could discuss, here’s one of the most basic but most universally useful: everything you buy for your office, at home or at a separate location, every training you attend, every promotional effort you make, may qualify as a deduction. That only works if you document everything, however. Even a simple spreadsheet will do the trick. Buy a couple of large envelopes (keep the receipt!) and label them for this sort of thing; once you’re in the habit, it’s easy to keep track of miscellaneous expenses this way.

As more and more business is done online, set up some sort of labeling system for emails acknowledging purchases (Gmail does this quite easily). And it’s fine if you buy printer ink or replacement cables from Amazon or any other dot-com, as long as you have some system in place to remind yourself come tax time. Most online vendors have easy access to that sort of information for years after you buy something, but that’s not particularly helpful if you forget to look for it so you can claim it. All of this may seem tedious, but organization and a paper trail are two of the most fundamental small business tax basics.

If your small business is truly “small,” either by design or because you’re just starting out, you may be able to simplify even this step by using the Schedule C-EZ instead. You may qualify for the Form C-EZ if your business had expenses of less than $5,000, you don’t maintain inventory throughout the year, and you don’t have employees. You can see the full checklist on the form itself if you’re curious whether this might be you.

Self-Employment Taxes

If you work or have worked for someone else, you probably know that the amount you actually get paid each month is quite a bit lower than the amount you make on paper. That, of course, is because your employer takes out mandatory withholding on your behalf to send to various government entities as demanded. (If your small business has employees, you’ll need to do this as well. We’ll get to that next time.) Federal income tax is a big part of that, but if you’re a sole proprietor, you’re paying that directly once a year. Your income from your business is your income, after all.

Another mandatory withholding is the combined Social Security and Medicare tax, sometimes called FICA on your paystub. Sole proprietors have to pay this as well, at exactly the same percentage as you would if you were working for someone else. The only difference is, it’s not being “withheld” from your paycheck. You take care of this along with your other taxes using the Schedule SE. There’s a short version and a long version, but you don’t have to figure that out ahead of time because they’re both on the same form and the instructions are big and clear along the top.

In terms of complicated tax stuff, this isn’t one of the hard parts.

Paying Quarterly

One way in which your sole proprietorship taxes aren’t quite the same as paying as an individual is in the required scheduling. Most of us only do our taxes once a year – hopefully sometime before April 15th. Of course, that’s something of an illusion… you’re paying federal income taxes from every paycheck. It’s just that your employer takes those out before you get paid. What we’re actually doing once a year is figuring what we OWE and comparing it to what we’ve already paid (or had paid on our behalf). It’s then that we either pay the difference or receive a refund.

As a sole proprietor, you’ll be doing something similar by paying your estimated taxes throughout the year. Usually this is done quarterly – every three months. There are a few guidelines to clarify who does and doesn’t have to do it this way, but if you run your own business, chances are good this means you. You’ll use Form 1040-ES to figure out your estimated amounts and where to send them. One reality of small business tax basics is that it’s always “tax time”!

You’ll get a decent idea of how much you can expect these quarterly estimates to be once you’ve done them a few times, but a good rule of thumb to start with is to make sure you’re saving at least 25% of your overall profits for these payments. That’s easy to remember – set aside a quarter of your profits to pay quarterly. (I assure you, the I.R.S. will give no quarter if you don’t.)

Local Wrinkles

Depending on where you live and do business, there may be state or local taxes or other requirements as well. Like with everything else, these will get easier the more you do them, but it’s impossible to say with any accuracy what you should be looking for in your area. If you hire a tax professional to handle such things, they should know these well already. If they don’t, they might be the wrong tax professional.

Small Business Tax Basics: Partnerships

As the name suggests, a partnership is the combined ownership of two or more people. There are three basic flavors.

1. The General Partnership.

These are fairly easy to set up. While partners have the option of creating substantial structure to how the business is run, the basic structure means all partners share unlimited control and unlimited liability. That means any partner in the business can make major decisions like making purchases or taking out business loans on behalf of the whole, with or without consulting the others. It also means every partner is liable for 100% of any debts or other obligations of the business, whether they were involved in whatever caused the problem or not.

As you might imagine, General Partnerships require a great deal of trust. This also explains why some of them have such complex arrangements about conflict resolution and agreed-upon steps for making major decisions and such.

General partnerships are taxed very similarly to sole proprietorships, with “pass-through income” and minimal additional paperwork beyond each partner’s Form 1040. The business will need to file a Form 1065 and each partner must pay self-employment taxes and estimated quarterly income taxes in most cases, just like if they were sole proprietors. Each partner must also complete a K-1, also known as Form 1041, which is essentially a worksheet to compute their share of that year’s profits or losses.

2. The Limited Partnership (LP)

In this arrangement, one partner holds more influence but retains greater liability for any debts or other bad things while the other partner (or partners) have less influence but limited liability. If this seems “unfair,” keep in mind that it’s called a “Limited” Partnership – as in, not a complete partnership. The details for all of this would, of course, be spelled out in the partnership agreement negotiated and agreed to by all concerned parties. (It’s not like anyone’s getting blindsided here.)

Under this set-up, the business completes a Form 1065 each year, and each partner a K-1. Other than that, the unlimited liability partner claims business profits as income on his or her 1040, just like sole proprietor. Also like a sole proprietor, the partner with greater influence pays self-employment taxes as well. Because this is a “pass-through” arrangement, they also have a good chance of taking that 20% deduction we discussed above.

How the “limited” partner is taxed is a bit trickier. They receive their compensation in the form of “distributions,” which are technically distinct from getting a paycheck. Like profits from owning non-controlling stock in a corporation, distributions are a form of “passive income” (because the partner receiving it doesn’t have control of the business, at least on paper). I’m not going to elaborate on the details here because (a) they only apply to a very small number of people, and (b) they make my brain hurt.

3. The Limited Liability Partnership (LLP)

In an LLP, all partners have equal control and equally limited liability. This structure has many of the benefits of a corporation in terms of protecting the owners, but doesn’t pay corporate income tax. In short, partners have most of the conveniences and tax advantages of being sole proprietors, but can generally only lose what they’ve put into the business. They aren’t liable for debt or damages beyond that. As long as they can deal with one another, this is the best of both worlds.

Like with sole proprietorships, profits from the business “pass through” to individual tax returns. Partners must pay self-employment taxes and quarterly estimated taxes. I.R.S. requirements for a Form 1065 for the business and a K-1 for each partner are generally the same. And, as with all partnership variations, any losses are deductible on individual tax returns. Here’s a small business tax basics tip, however: you’d prefer NOT to have losses. (Aren’t you glad you have me to explain these things?)

4. Local Wrinkles

Keep in mind that all of this is general information related to federal small business tax basics. Your specific small business may trigger different rules or requirements or may be exempt from certain liabilities. It’s always worth reading through those I.R.S. instructions, and there’s no shame seeking the guidance of a tax professional. Plus, different states have different definitions and requirements for small businesses within their realms. Some are more “business-friendly” than others, and some have different ideas about how things should work, fiscally-speaking.

I’m not trying to scare you off of starting your business if that’s your calling; just letting you know some things of which you should be aware once you do.

Small Business Tax Basics: C-Corporations (aka “C-Corps”)

C-Corporations draw the clearest lines between the company and the individuals running it. On the one hand, they provide substantial protection for owners should things go south; the company may suffer, but the individuals at the top aren’t personally liable in most situations. On the other hand, C-Corporations require the most paperwork and reporting of the structures discussed here, and tax management is more challenging.

The profits of C-Corporations are taxed twice – first when they make a profit (hopefully) and again when shareholders file their personal tax returns. This “double-taxation” is the reason many small businesses try to avoid this structure, preferring the LLC or S-Corporation (see below) instead, if practical. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) eliminated scaled corporate tax rates, which prior to 2018 had gone as high as 35%. At the moment, all C-Corporations pay a flat income tax rate of 21%, regardless of the size of their business or their profits. This is commonly done using Form 1120.

Employees of C-Corporations are subject to withholding and must pay income taxes like anybody else. Stockholders are required to report income from dividends separately. They’ll usually receive an annual 1099-DIV, just like some of get from our banks if we’ve earned any interest that year. If you’ve ever received a 1099 or variation thereof for freelance work or other forms of contract labor, you’ll notice the forms are quite similar. Corporations are responsible for getting these out in a timely manner, as well as reporting everything to the IRS using a Form 1096 – at which point it gets rather involved and a bit confusing if you’re not a full-time accountant or tax professional.

Some corporations get creative about avoiding self-employment taxes by paying lower salaries and distributing profits more actively via dividends. There are limits to how far this can be taken without violating the law, but it’s worth being aware of if you’re considering this structure for your business. And of course C-Corporations are better able to draw investors and thus raise funds more readily, allowing for greater expansion and economies of scale. There’s a reason big companies tend to be C-Corporations, but you don’t have to be big for this structure to work for you.

Need a Tax Preparation Firm? Find it with Taxry!

Small Business Tax Basics: S-Corporations (aka “S-Corps”)

An S-Corporation is not a business structure, but an option for business tax management. The defining feature of an S-Corporation is that it elects to “pass-through” its profits to be taxed on the individual tax returns of its owners, just like a sole proprietor or partnership. They are, of course, responsible for self-employment taxes and all the usual stuff that goes with “pass-through” profits. Ownership still maintains many of the protections of a C-Corporation, however, limiting their personal liability for business losses or other bad things which might occur over the years.

Because there are obviously substantial advantages to this structure for many small business owners, it comes with more limitations and definitions than most other options. S-Corporations may have no more than 100 shareholders and only one type of stock, and shareholders must be U.S. citizens or legal residents. Still, they’re a very popular option among small business owners, and for good reason.

C-Corporations, you may recall, file Form 1120 for purposes of computing corporate federal income taxes. S-Corporations don’t pay corporate federal income taxes, but nevertheless file a Form 1120-S so the I.R.S. can keep track of things and compare the info submitted there to that reported by the various individuals receiving those “pass-through” profits. S-Corps can also do some of the same salaries vs. dividends shenanigans that C-Corporations love, but with the same limits on just how far they can go.

Feel free to stretch the system, my friend, but don’t color completely outside the lines. It’s not worth it, I assure you.

What Else Do I Need to Know?

Next time, we’ll look at what you’re expected to do in terms of payroll taxes if you have employees. We’ll also highlight some of the most common (but easily overlooked) small business tax deductions you should know about. In the meantime, you should get back to work – it’s not easy running your own business, after all!